Worth the Money: Energy Saving Upgrades that Quickly Pay for Themselves

Last updated July 2025

Most of us want to reduce our energy usage, regardless of upfront costs, but limited budgets prevent many homeowners from buying expensive improvements such as solar energy systems or large-scale green-oriented renovations. Here are affordable-to-most projects that will, in relatively short periods of time, pay for themselves via lower utility bills. Click here for further info on our sample home and how we calculated estimates of energy use and possible savings.

Keep in mind that making simple repairs or improvements and changing wasteful habits will yield enormous energy savings for most families. Click here for a list of basic steps that cost nothing or little to do but fix common sources of home-energy waste.

Add Insulation

As we discuss in our section on insulation improvements, sealing leaks and improving attic insulation can provide big-time energy savings.

Available incentives and lower energy bills quickly wipe out upfront investments, making these no-brainer projects for most area homeowners.

All structural elements enclosing your home’s living spaces should be insulated. It’s most practical to add insulation when a home is built or during renovations. Otherwise, accessibility drives costs and often determines what’s worth doing.

Because warm air rises, your attic is the front line in the battle to conserve energy during winter. And because most attics are unfinished and contain a lot of empty space, adding a thick layer of insulation is easy.

Unheated areas underneath ground floors (crawlspaces, basements) are also good places to add insulation. Crawlspaces should be dry year-round (moisture causes insulation to deteriorate), and a vapor barrier should be placed on the crawlspace floor.

Cost: Attic insulation jobs typically cost $1,500 to $3,000. A tax credit will pay for 30 percent of most insulation improvement projects but that incentive goes away at the end of 2025. North Shore Gas and Peoples Gas have generous rebate programs for insulation improvements. Costs to add wall or floor insulation heavily depend on access. Click here for more discussion.

Our energy savings: $109 per year after adding attic insulation; $150 per year after also adding insulation to unfinished basement walls.

Need a New Furnace? Go for Energy Efficiency

Gas and oil furnaces are rated by annual fuel utilization efficiency (AFUE). Simply said, a 90 AFUE furnace uses 90 percent of its fuel efficiently and wastes 10 percent.

New furnaces sold in this region must have a minimum AFUE rating of 80, meaning lots of the heat goes up the chimney. More efficient residential furnaces have AFUE ratings of 92 to 98, but because they’re more expensive, many homeowners replace broken furnaces with minimally efficient models.

That’s short-sighted since the resulting energy savings from buying an efficient model will quickly pay off its extra cost. For example, replacing an old 80 AFUE furnace with a new, efficient 98 AFUE model will save about $225 annually off our sample home’s heating bills.

When selecting a furnace, also consider features like variable-speed blowers and two-stage burners. These setups have higher price tags, but operate furnaces at different output levels, depending on need. By helping maintain consistent temperatures throughout different areas of homes, they can decrease heating and cooling waste by about 10 percent, plus minimize systems cycling on and off, which contributes to wear and tear.

For the ultimate energy saver, replace your furnace with a heat pump. These devices are basically air conditioners that can operate in reverse to also heat buildings. New heat pumps are extremely energy efficient and quiet.

Cost: It costs about $1,500 more to install a 97+ AFUE gas furnace instead of an 80 AFUE model, but rebates from some local utilities can reduce that upfront cost differential to $1,300 or less.

Our energy savings: $159 per year by switching to a 92 AFUE furnace, $192 per year for a 95 AFUE model, $224 for a 98 AFUE model.

Heat or Cool One Room at a Time

Portable heaters are very inefficient. To improve heating or cooling in one room, on one floor, or in an addition, install a mini ductless unit, or “mini-split.” Common in Europe and hotel rooms, these devices allow you to control temperatures in a single space. Because they use very little electricity and don’t lose a lot of energy transmitting air through ductwork, they are highly energy efficient. And by heating and cooling rooms only when in use, you’ll see significant savings.

Cost: $1,000-$4,000 for one room, depending on what you buy and who installs it; click here for for possible rebates.

Our energy savings: Not a practical retrofit for our sample house, but ductless units typically consume 30 percent less energy than conventional ACs and heat pumps; then save even more if you use them only as needed.

Get a Programmable Thermostat

Programmable, or “smart,” thermostats can save a lot of energy. If your home is unoccupied during the day, you can save 10 to 25 percent per year on heating costs by letting the temp decrease while you are away and lowering it again when you’re snuggled under blankets at night; you’ll get similar savings during summers by letting AC temps increase when you’re not home. Unfortunately, many homeowners who have programmable thermostats don’t actually program them. New models make programming a snap, and some even program themselves.

Cost: Free if you already have one and don’t program it; Nest’s popular models run $99-$279; a professionally installed thermostat will cost $100-$400.

Our energy savings: $139 per year.

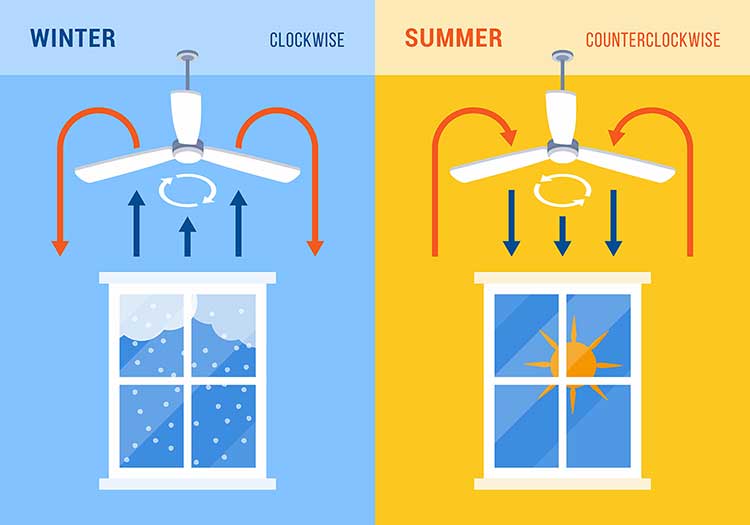

Use Fans

By constantly circulating air, fans reduce heating and cooling costs. For ceiling fans, spin the blades clockwise in winter to pull cooler air up, which pushes warmer air down the walls to you. During the summer, flip the switch to turn fans counterclockwise.

If you need ceiling-fan installation help, click here for ratings of local electricians for quality and price.

Cost: Good pedestal fans cost less than $75; most ceiling fans cost $100-$300, plus $100-$200 for installation by a licensed electrician.

Our energy savings: $59-$99 per year.

Get a Heat Pump Water Heater

Some new water heater models use heat pumps to extract warmth from the air around them and dump it into their tanks. This is a far more energy-efficient process than generating heat from a gas burner or electrical resistance. By replacing an old unit with a heat pump-equipped water heater, most homeowners will cut water-heating costs by half, compared to a new gas model, and by two-thirds, compared to electric.

Although heat pump-equipped units cost more than conventional water heaters, utility savings quickly recoup extra costs. Given their enormous potential benefit, it’s disappointing so few companies recommend these energy-thrifty devices to their customers.

Cost: Heat pump models are usually $300 to $500 more expensive than comparable conventional units but resulting energy savings will quickly recoup higher project costs. You can use a federal tax credit to recoup 30 percent of the price tag of a new heat pump water heater but that incentive goes away at the end of 2025.

Our energy savings: $94 per year.

Don’t Want a Heat Pump Water Heater? At Least Get an Energy Efficient Replacement

While Energy Star-certified water heaters cost about $175 to $300 more than comparable non-certified ones, rebates can erase that extra expense. Even without an incentive, the resulting gas or electricity savings will easily pay off a higher upfront price tag over the unit’s lifespan. If you want to stick with gas, tankless water heaters also provide energy savings.

Cost: $175-$300 more than less efficient models but most homeowners can get rebates to cover extra costs.

Our energy savings: $20-$62 per year.

If You Can’t Repair an Appliance, Spend Extra for an Efficient Replacement

The expense of replacing functioning appliances with new, more energy-efficient ones seldom nets you overall financial savings. But if an existing appliance needs repair, compare the repair cost to the price of a replacement minus expected energy savings.

Calculations at EnergyStar.gov let you compare annual operating costs of efficient and inefficient appliances according to how much you use them and how long you expect the new unit to last, among other variables. When doing this math, make sure to factor in any rebates you can get.

If you decide to replace a busted appliance, go for an Energy Star-certified model. Although they are more expensive than comparable less efficient options, your energy savings will make up for that difference.

Also consider swapping out a gas range with an all-electric model; there are incentives to help pay for that. Click here for advice on selecting appliances, plus ratings of stores for quality and price.

Cost: With so many models for sale across wide price ranges, we can provide only rough estimates, but compared to less efficient, comparable models, Energy Star-certified refrigerators typically cost $200-$300 more; dishwashers $275-$350 more; clothes washers $100-$125 more; and dryers $325-$400 more. Rebates might offset any price step-ups.

Our energy savings: $6 for dishwasher; $36 for clothes washer; $25 for dryer.

Landscaping

If you plant trees that lose their leaves each autumn on the south and west sides of your home, they’ll provide shade during the summer; during the winter, their bare branches will allow sunlight to warm the joint. Planting shrubs or evergreen trees on the northern side of your property will provide a windbreak and reduce heating costs.

Cost: Depends on how much you do and setting of home.

Our energy savings: $40-$150 per year.