Window Shopping Guide

Last updated May 2023

The type of windows you buy will affect your home’s appearance, the amount of light admitted, your comfort, and energy savings. Plus, some windows last longer than others.

The type of windows you buy will affect your home’s appearance, the amount of light admitted, your comfort, and energy savings. Plus, some windows last longer than others.

Start by visiting installers’ showrooms. Ask staffers to explain features and installation techniques, and grab catalogs. If you are adding or enlarging windows, or doing new construction, get creative ideas online and from home design magazines.

Consider which windows are appropriate for your house’s architecture, and, if you live in a historic district or a neighborhood with a homeowners association, find out what’s allowed. For example, preservation officials or homeowners association rules might ban vinyl windows or specify certain types of window muntins (grids). Ignore them and you might have to tear out what you install.

Styles

The most common window styles are:

- Double- and single-hung. These types look the same, but only the bottom sash moves in single-hungs. You can crack them for ventilation and lock in that position, with window pins for security. Tilt-in models are easy to clean on both sides, though only half the window area can be open at any time.

- Casement. These outward-swinging windows open fully for ventilation and boast unobstructed views. But the cranking hardware often malfunctions, particularly on large units. Because casement windows also provide too-slow escape routes in case of fire, they shouldn’t be installed in bedrooms.

- Awning and hopper. Awning-style windows swing out at the bottom; hoppers swing in at the top. Both types of rectangular units (imagine casements turned on their sides) can be inset at the top of foundation walls to provide light and ventilation to basements.

Frame Materials

Frame Materials

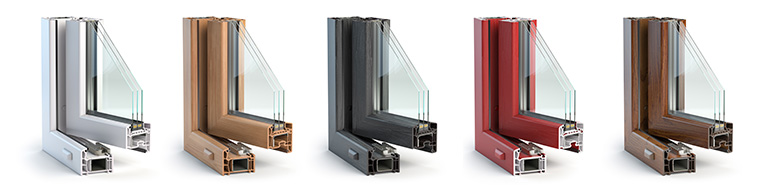

All window styles are available in different materials, including wood, vinyl, fiberglass, and aluminum. The most significant differences among them aren’t materials but construction quality. A cheaply made wood frame won’t hold up as well as a top-quality vinyl or fiberglass one, and vice versa. Aluminum is less popular than it was before because it is a poor insulator and sometimes suffers from condensation in cold climates.

There’s a wide price range for all materials, but vinyl is usually the least expensive, wood is priced mid-range, exterior-clad wood more expensive, and fiberglass models the priciest.

Other things to know:

- Vinyl—Earlier vinyl windows expanded and contracted too much during temperature swings. Modern models usually don’t, as manufacturers usually stick to light colors that don’t overheat. Still, this limits design options. Frames with welded corners are the sturdiest and most energy efficient.

- Wood—A traditional choice, these provide good natural insulation and can be milled to provide classic architectural detailing that complies with historic district and neighborhood association restrictions. Their interiors usually come factory primed, ready for a finish coat in any color. The outside-facing wood also can be primed and ready for paint or covered (“clad”) in aluminum or vinyl; the latter option protects windows from the elements but limits color selection. While paintable windows are versatile, they’ll require scraping and fresh coats every few years.

- Fiberglass—This grainy synthetic is the most durable and strongest type, making it a good choice to hold large panes of glass and groups of several windows. It can be extruded into slimmer profiles than vinyl, making it a good choice for frame-plus-sash replacements. It can be painted and is available with interior wood veneer facings.

Besides choosing your material, you’ll need to decide on style details, such as the thickness of your frames, grids (muntins), and hardware.

Replacement Techniques

If you’re replacing windows, there are three installation types:

Sash Pack

Consider a sash pack—the least expensive way to get new windows—if your existing frames and trim are in good shape, and your primary goal is better energy efficiency or draft reduction. Typically, the old sash and tracks are removed, and jamb liners are installed against the sides of the frame. Installers seal and secure the new sash.

Some manufacturers carry over 100 stock sizes for sash packs; fabricate custom sizes; and offer many colors, cladding, tilt-in hardware, divided-light grills, and other features. Some sash-pack sellers provide very good instructions for homeowners who want to save money by installing windows themselves.

Frame and Sash

The more common (and more expensive) option is a fully framed sash unit that slips into the existing window frame after the old sashes and tracks are removed. Because the existing frame and trim stay in place, they need to be in good shape.

The key here is the amount of space between the old and new frames. A good match will produce a close fit, with no two-by-fours added to pack out and significantly downsize the opening. Glass area may be reduced by an inch or so, but not by several inches. Small gaps between old and new frames are fine; they can be insulated and existing trim can be built up with narrow strips that blend into the overall façade. Installers should tuck in loose-fill insulation or spray in low-expanding foam. (Standard foam has enough pressure to bow the jambs.) On the other hand, if the fit leaves large gaps, typically wide boards or aluminum panels are required to bridge the openings; the result looks out of scale and doesn’t fit in with the façade.

Full Window

Replacing everything is the most expensive approach. The old window is pulled out, damaged framing repaired or replaced, and a new window is installed. This is the only option if the framing needs to be significantly altered. It also avoids the reduction in glass area produced by the frame-and-sash approach.

If your old windows are stock sizes (most are), you shouldn’t need custom construction. Window manufacturers’ catalogs often list 75 or more sizes just for double-hungs. For the rough opening (the distance between framing members that allows for shimming space), widths range from 24 inches to 48 inches, and heights range from 36 to 72 inches.

Energy Efficiency

Modern windows reduce your home’s wintertime heat loss, enhance its wintertime heat gain from the sun, and suppress its summertime heat gain. Within each window style and construction option, you’ll find windows providing different levels of energy efficiency.

In general, the more efficient the window, the higher its price. By choosing efficient windows, you conserve energy, reducing your energy usage and saving you money.

In addition to saving energy, more efficient windows will help keep your home more comfortable by eliminating cold areas around windows. You will also be able to maintain a higher and more comfortable humidity level during winter months than if cold dry air infiltrates your home and window surfaces are cold enough to collect condensation.

Here’s how to compare windows’ energy conservation performance:

Construction and Insulation

Modern windows have two or three panes of glass, with air or an inert gas filling space between panes as an insulator. Usually one or more of the panes is glazed with a thin, transparent metal (“low-E”) coating to minimize heat radiation. In high-quality windows, the frames are made with materials that are poor heat conductors, as are spacers around the edges of the frames that separate layers of glass.

U-Factor

This measures how easily heat passes through the window. To minimize heat loss, look for windows with a low U-factor. Old single-paned aluminum-framed windows might have a U-factor of about 1.3; some new high-tech windows have U-factors as low as 0.1. All new residential windows should have U-factors of .27 or lower.

Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC)

This expresses the fraction of the sun’s radiation a window admits. In cold weather, a high SHGC number is desirable for windows that get strong sun exposure. The heat a home takes in through a sunny south-facing window may be great enough to more than offset heat loss through the window, making the window better than a well-insulated wall from an energy conservation standpoint. But in warm weather a high SHGC number in sunny windows is undesirable, as heat from the sun raises indoor temperatures. The ideal solution is to have high SHGC ratings on south-facing windows, which get direct exposure to the sun when the sun is low in the sky in the winter, and then shade these windows in the summer with a roof overhang or trees.

In general, as U-factor goes down (when more effective low-E coatings are added to the glass), so does the SHGC measurement. For a south-facing window you may decide to sacrifice some ability to prevent heat loss in favor of a window with high solar heat gain potential. An old window with a single clear pane of glass with no special low-E coating might have an SHGC rating of about 0.70; a double-glazed window with low-E coating on both panes might have an SHGC of about 0.35, meaning it transmits about half as much solar heat as the old model.

Air Leakage

Windows should have an air-leakage rating of 0.3 or less. This rating is measured in cubic feet per minute per square foot of window (cfm/sq. ft.) to gauge movement of air (convection) between the inside and outside of a building through cracks in and around the window frame.

Using This Info to Select the Right Products

You should find a window’s U-factor and SHGC measures on a label developed by the National Fenestration Rating Council (NFRC); a sample label appears in the figure below. Don’t buy a window that lacks this label. Window manufacturers aren’t required to test their windows for air leakage, or display it on the label; testing and reporting it are voluntary.

If you’re seeking to minimize your home’s energy usage no matter the cost, buy windows with non-metal frames and triple panes. But most homeowners will want to do a bit of cost-benefit analysis. Many window suppliers offer online calculators to estimate the energy cost consequences of windows with different efficiency ratings. The Efficient Windows Collaborative has a Window Selection Tool that provides general estimates on how various window types will affect your utility bill.

If you’re seeking to minimize your home’s energy usage no matter the cost, buy windows with non-metal frames and triple panes. But most homeowners will want to do a bit of cost-benefit analysis. Many window suppliers offer online calculators to estimate the energy cost consequences of windows with different efficiency ratings. The Efficient Windows Collaborative has a Window Selection Tool that provides general estimates on how various window types will affect your utility bill.

Despite what window suppliers might tell you, even if your current windows are extremely inefficient, you’re unlikely to save enough money from lower utility bills to offset window replacement costs. Even basic new windows are expensive—$500 or more per opening, but most quality models cost $1,000 and up—and models featuring maximum energy-saving features cost more than double that. Even if new windows can cut your heating and cooling bills by 15 percent (unlikely for most homes), you won’t save enough to make replacements a “good investment.”

There are other issues to consider. For example, the extra energy savings yielded by triple glass compared to double glass might require you to accept lower light transmittance, greater visual distortion, heavier and harder-to-move sashes, increased risk of breakdown of seals and the resulting condensation between panes (because there are two sets of seals rather than one), and less attractive grids (in triple-glazed windows, the grids between panes must generally fit into a smaller space).

Other Considerations

In addition to thinking about energy savings consider:

- How much you value the increased comfort and improved appearance the windows will provide.

- How much the window improvements are likely to increase your home’s resale value.

- How many years you expect to live in your house.

Effect on Sunlight

The reason we have windows is to create views and admit sunlight. But all of them don’t do this equally. Light passing through a window is affected by the glazing material (glass or plastic), number of layers of panes, and any coatings applied to the panes. Window-makers use “visible transmittance” (VT) to indicate how much light windows admit. VT ranges from more than 90 percent for clear glass to under 10 percent for windows with highly reflective coatings on top of tinted glass.

You may have to sacrifice some visible light to achieve energy efficiency, meaning your view won’t look as bright as it otherwise would.

Durability

Durability

Depending on construction, windows can last for decades—or rot and fail within a few years. Start by checking out Consumer Reports’ window ratings, which periodically test about a dozen best-selling models for resistance to wind and rain. But since Consumer Reports tests a fairly small number of models, you might have to do some homework.

Check guarantees. Better-sealed window units tend to come with 20-year (or more) warranties and don’t prorate reductions in the covered value as time passes.

Consider the claims salespeople make about durability. Talk to several installers and get their opinions on which window brands are most reliable.

Since most windows fail due to weak corner joints and moisture, ask about these hazards. To avoid moisture accumulation in wood windows, buy windows with drainage holes and spaces for air circulation.

Vinyl windows require no maintenance, as do the vinyl- or aluminum-clad areas of wooden ones, so long as there aren’t any exposed wood surfaces.