Discover Offers Free and Simple Way to Opt-Out of Popular People-Search Websites

Last updated June 7, 2022

As Checkbook discussed in a previous report on how to guard your online privacy, our daily online life is being compiled and sold or traded by thousands of companies, usually by unregulated data brokers.

Listen to audio highlights of the story below:

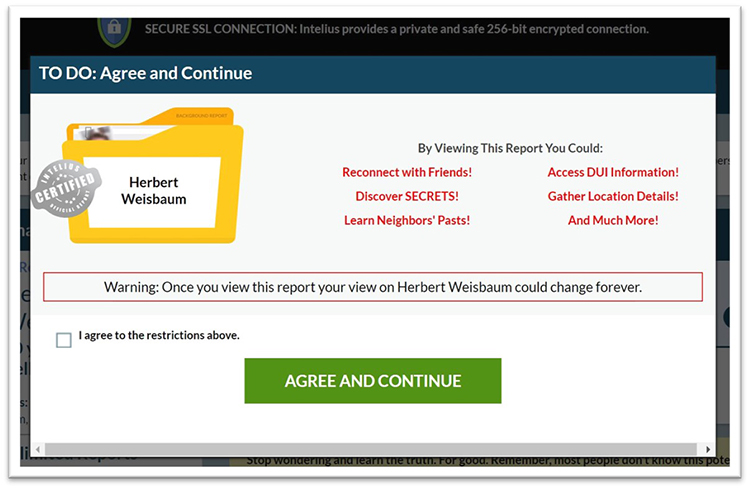

This commercial surveillance includes selling your personal info to a variety of people-search websites that anyone can access for a small fee. These sites market themselves in various ways, including to do a background check on a babysitter or find a long-lost friend or relative.

According to research by Discover Bank, most people (83 percent) are concerned about misuse of their personal information. Nearly a third of those it surveyed (31 percent) indicated they thought they have no control (or not much control) over that data.

“Consumers today worry about their personal data ending up in the wrong hands,” said Shannon Kors, vice president of product and marketing at Discover.

And those concerns are valid. In a matter of minutes, someone can search for your name and get:

- Your age and year of birth

- Education

- Home address and value of your property

- Previous places you’ve lived

- Home, work, and cell phone numbers

- Email addresses

- Social media accounts

- Current and previous employers

- Business licenses associated with your name

- Marriage and divorce records

- Relatives and their contact information

- Criminal or traffic violations

- If you’ve declared bankruptcy

- Judgements and liens

Most consumers who responded to Discover’s survey (72 percent) said they were interested in removing their personal information from these people-search sites. Only 64 percent knew how to do that.

Most consumers who responded to Discover’s survey (72 percent) said they were interested in removing their personal information from these people-search sites. Only 64 percent knew how to do that.

Many people-search sites make it possible to opt out of having your information collected and shared, but that can be “time consuming, confusing, and costly,” Kors said.

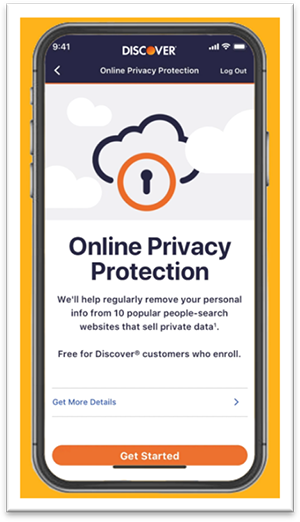

Discover recently launched a new benefit for its credit card and bank customers. It says its “Online Privacy Protection” program makes it easy to remove personal information from 10 popular data-collecting websites, including Spokeo, Intelius, and ZabaSearch. The free service is accessed through the Discover mobile app.

Does This Matter?

For those who need to guard their personal information, such as survivors of domestic abuse, opting out of this data sharing is crucial.

For others, by reducing the number of websites that can share your personal information you might lessen the “creepiness factor” of so much of your data being easily accessible. It could also reduce unwanted phone calls and junk mail.

“For some people, they don’t care if everyone knows their home address, but for others, it’s a really big deal, and it’s a true safety issue,” said Pam Dixon, executive director of the World Privacy Forum. “So, it’s actually really important that people who have safety concerns are able to remove their information from all of the public record, easily accessible internet sites.”

Removing your information from people-search sites might lower your risk of identity theft, but it won’t eliminate the threat—something Discover makes clear to customers who sign up for its program.

“It’s one more tool” to help you manage and protect your identity, “but it’s not a brick wall,” said James Lee, COO of the non-profit Identity Theft Resource Center.

That’s because most identity thieves go on the dark web and buy information that’s been stolen in data breaches to commit their crimes.

“Billions of pieces of information about people are readily available, and that’s where criminals go,” said Lee. “So, restricting the information from legitimate data brokers and look-up companies isn’t really going to have much of an impact on the identity crime wave that we’re seeing right now.”

My Test Drive of the New Program

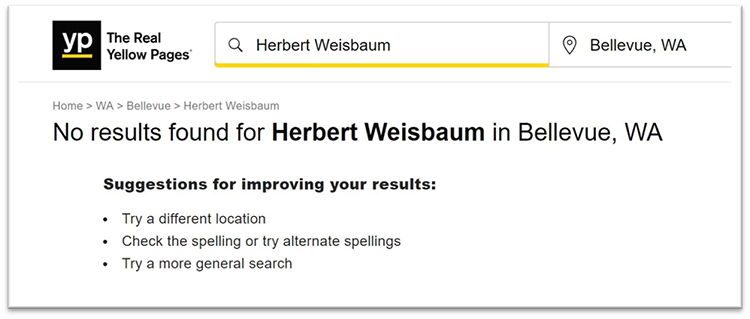

I opened a small savings account at Discover and downloaded the bank’s app. After launching it, locating the “Online Privacy Protection” tab, and agreeing to the terms and conditions, the dashboard reported that it had sent opt-out requests to nine websites that had my information: Addresses.com. AnyWho.com, InstantPeopleFinder.com, InstantCheckmate.com, Intelius.com, TruthFinder.com, USSearch.com, YellowPages.com, and ZabaSearch.com. For some reason, no opt-out request was sent to Spokeo, the tenth site at which Discover claimed it would remove my personal info.

After waiting a couple of days, my online privacy dashboard indicated that all nine opt-outs were completed.

To make sure my information was really gone, I checked those nine sites, and found that my information was no longer available on any of them.

Discover’s tool uses BrandYourself, which calls its services “Reputation Management Software,” to handle the opt-out processes. After sending initial opt-out requests, BrandYouself will automatically scan the 10 websites every 90 days to see if that data re-appears. That’s likely to happen; if it does, another opt-out request will be submitted.

Erroneous Information

Before I used Discover’s opt-put service, I signed up (and paid the subscription fee) for several of the most popular people-search sites to find out what info they had on me. I was surprised to see significant errors, including: Email and social media accounts I never had; property listings in Seattle and New Jersey for homes I never owned; the address of my brother’s old apartment as my previous residence (I never lived there); and an old address (from 1981) listed as my current address.

The biggest surprises: My wife and I have a child (we do not) and our house has a swimming pool (I wish).

I also found erroneous information linked to my wife, including a cell phone number she never had (with service from a wireless carrier she never used), and a Twitter account she does not have. My wife isn’t on Twitter.

These search sites post disclaimers that they do not guarantee the accuracy of the information they gather—you pay your money and take your chances.

“It is unacceptable that there were this many significant errors,” said Dixon. “What if someone relied on this bad data? And this is just two records out of many thousands.”

With a credit report, if you find a mistake, the credit reporting agency is required by law (the federal Fair Credit Reporting Act) to investigate and correct the error. But that law does not regulate data brokers.

With a credit report, if you find a mistake, the credit reporting agency is required by law (the federal Fair Credit Reporting Act) to investigate and correct the error. But that law does not regulate data brokers.

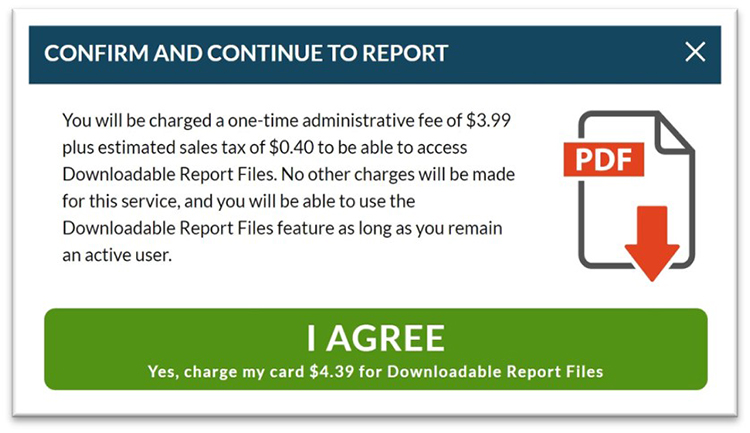

Note: Some of these sites have ways to upsell you to spend more. Intelius charged me $4.39, on top of its $27.27 subscription fee, to download my report. Other sites had additional fees for added searches, such as judgements and liens, or professional licenses.

A Good Start

The World Privacy Forum and Identity Theft Resource Council praised Discover for offering this free opt-out service to its customers. It can’t stop the deluge of information collected on all of us, “but if you can tame it down to a dull roar, it’s actually very helpful,” Dixon said.

Privacy experts believe the optimal solution is for Congress to pass a national privacy law, something it has been unable to do for decades.

“We need to mandate that consumers have more visibility and more control over their data,” Lee said. “Data brokers, the companies that collect and sell our information, should be required to show us what information they have about us, allow us to challenge the accuracy, and make sure it’s correct. We should also be able to make it known if we do not want our information sold or used for a particular purpose, particularly marketing.”

The European Union passed its General Data Protection Privacy Law in 2018. It requires all companies doing business in the E.U. not to look at, collect, store, or sell someone’s personal data unless there is a “legitimate” need for it (as spelled out in the law) and that person has given “unambiguous consent” to process their data.

This Just In

Could Congress be ready to pass the country’s overall privacy protection legislation? A bipartisan draft of the “American Data Privacy and Protection Act” was released on Friday, as reported by Politico. It would provide “a national standard on what data companies can gather from individuals and how they can use it.”

The authors of the draft privacy bill called it a “critical milestone…a comprehensive data privacy framework has been years in the making.”

Contributing editor Herb Weisbaum (“The ConsumerMan”) is an Emmy award-winning broadcaster and one of America's top consumer experts. He is also the consumer reporter for NW Newsradio in Seattle. You can also find him on Facebook, Twitter, and at ConsumerMan.com.