Last updated December 2020

Warranty companies and their public utility partners pitch nightmare scenarios. But these programs stink.

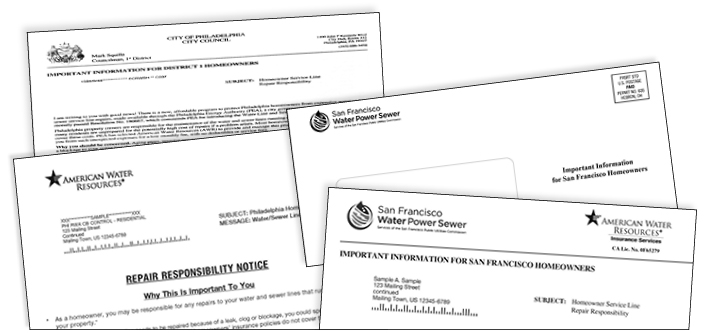

Millions of U.S. homeowners regularly receive official-looking notices such as the following, sent to a Checkbook staffer:

“Recently, we wrote to you about your responsibility for the exterior water line on your property… Because you own this line, an unexpected breakdown could cost you thousands in out-of-pocket expenses to replace if a breakdown occurs… That’s why we’ve partnered with HomeServe, a premier provider of home emergency repair programs, to offer eligible customers [coverage] to help protect against these unexpected costs.”

Offers like this often come on official letterhead in envelopes bearing utility company logos. They contain ominous warnings that you, the homeowner, are responsible for repairs to water and sewer lines on your property. The clincher: If there are problems, “you could spend thousands of dollars to fix them, as most standard homeowners insurance policies do not cover these repairs,” warned one very-official-and-serious-sounding “Repair Responsibility Notice.”

Calls and emails from subscribers and queries on neighborhood message boards indicate that these notices often convince homeowners that they are receiving warnings about impending defects on their properties that need addressing. Why else would their utility companies issue such dramatic warnings?

Although these mailings seem to come from their utilities, they’re really pitches from third-party companies. They’ve struck sketchy partnership agreements with utility companies allowing them use of their names and logos to hawk (in our view, lousy) warranty coverage.

These ploys work: More than 7 million U.S. homeowners have purchased plans offered by the two largest warranty outfits, American Water Resources (AWR) and HomeServe. With marketing help from utility companies, these outfits pull in $900 million a year.

Nationally, these deals are widespread. The water utilities serving Baltimore, Cleveland, Louisville, Memphis, Nashville, Newark (N.J.), New York City, Philadelphia, Orlando, Salt Lake City, San Diego, San Francisco, and large swaths of the Washington, D.C. area have signed on to help private companies sell warranty plans.

AWR and HomeServe warn of dramatic potential costs if you don’t protect yourself with their plans. HomeServe’s website warns of an average $2,585 cost to replace a water line; $3,389 for sewer. Pivotal Home Solutions, an AWR subsidiary, pegs the “typical” cost of repairs higher still: $3,500 for water, $8,500 for sewer. And a video presentation used by HomeServe to recruit utility companies features a horror story from Niagara Falls, N.Y., where a couple’s burst water and sewer lines caused $20,000 in damages.

Our research finds that few homeowners ever have to deal with expensive water or sewer line repairs or replacements. While the warranty policies they can buy are inexpensive—most cost $4 to $13 per month—we found they’re still bad deals.

Why are utilities and municipal governments helping warranty companies to scare the public into buying these lousy plans?

The disappointing, unsurprising answer: money, lots of money. The utilities that sign on to help sell these warranties get generous shares of the premiums, which can add up to millions each year.

Even if your community’s water and sewer utility hasn’t yet joined this game, that could soon change. HomeServe’s 2020 annual report to shareholders said its growth strategy relies on adding partnerships “to reach the over 50% of homeowners who have yet to see a HomeServe offer.”

Selling Unwarranted Fear

Warranty companies warn of a potential catastrophe lurking under your property that might cost thousands of dollars to fix.

What are the chances a water or sewer line will need to be repaired or replaced? The warranty companies wouldn’t tell us.

“It’s hard to say. There are so many factors. I can’t tell you,” said Myles Meehan, a spokesperson for HomeServe. When we asked AWR, it declined to answer (and didn’t respond to 17 of 19 other questions we sent).

Our research reveals it’s an unlikely problem. Even if you need a repair or replacement, costs likely will fall well short of the thousands of dollars cited by the warranty companies.

Most municipalities require building permits before residential sewers are replaced. We searched the online permit records for San Francisco and dug up similar data from other large cities and found scant evidence that this is a common job at all:

- Our review of San Francisco’s permits in 2019 found that it issued only 369 water and/or sewer line restorations or replacements—out of the 112,115 single-family homes served by the city’s utility company. The chances of needing a restoration or replacement there was only 0.3 percent.

- Minneapolis officials told us they approved only 667 work permits involving home sewer laterals in 2019. That works out to a rate of 0.7 percent of the city’s approximately 100,000 sewer lines serving homes there—and because the city didn’t exclude permits for new construction from its counts, 0.7 percent is overstating the chance of trouble.

- Only 233 customers of the Boston Water and Sewer Commission in 2019 tapped its financial assistance program set up to help defray the cost of replacing or repairing sewer laterals. That was 0.3 percent of its 76,821 residential customers.

- On the California Department of Insurance website, we found a 2015 rate filing disclosing frequency of claims from Virginia Surety, which underwrites AWR’s plans. It reported that only 0.7 percent of its customers per year filed sewer line claims. AWR spokesperson Alicia Barbieri told Checkbook that was the last rate filing on record and it “is no longer applicable.” Nevertheless, that low claims rate jibes with the more recent less-than-one-percent incidence we found in other regions.

- Claims data from an interoffice memo obtained by Checkbook regarding the Washington [D.C.] Suburban Sanitary Commission’s partnership with HomeServe indicated that only 4,450 exterior water and sewer claims were made from the 126,207 plans purchased during the program’s first two-and-a-half years, an annualized incidence rate of 1.4 percent. (In 2019, after HomeServe purchased CroppMetcalfe, a large plumbing outfit operating in the Washington area, WSSC let its partnership with HomeServe expire. WSSC did not respond to our request for an interview.)

- The Philadelphia Water Department issued 2,459 “Notices of Defect” in 2019 for residential sewer laterals that the department discovered were in need of repair. That was 0.5 percent of its 481,728 customers. The Philadelphia Energy Authority (PEA), an independent city agency, actually collects precise claims data on the 83,000 Philadelphia homeowners who so far have signed on for coverage with AWR. But the PEA and AWR refused to release those data to Checkbook, claiming confidentiality. Checkbook appealed that denial under the Pennsylvania Right-to-Know Law, but the state’s Office of Open Records, unfortunately—and, in our view, wrongfully—determined that the public has no right to know about these facts.

Because permit info available online typically offers few details on jobs, examining them is arguably an imperfect yardstick. As much as possible, in our study of permits issued in San Francisco we included in our counts only permits that indicated repairs for what looked like owner-occupied houses and condos, which are the types of properties eligible for warranty plans. For example, we used Google Street View, Zillow, and other resources to eliminate permits issued for commercial properties and large apartment buildings, and we didn’t count permits for remodeling or new construction projects.

Other research shows that water lines can be trouble-free for years. A study done by Juneseok Lee, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Manhattan College, and co-authored with Meehan of HomeServe, which provided the data, looked at more than 47,000 water line replacements or repairs that HomeServe paid to fix over 10 years. It concluded that “it is not a question of if the piping will fail but rather when.”

However, that report’s findings indicate that when is likely a long, long time away. It found that lines made of copper, the most common material used for water lines, typically last 30 to 80 years. Galvanized steel pipes—also common—usually last even longer: 40 to 100 years. Even comparably weak plastic pipes (such as PVC and polyethylene) last 20 to 40 years. And because the study looked only at pipes that failed, your pipes may last a lot longer than these estimates.

Bottom line: Even if you own a house for decades, your odds of having a catastrophic water- or sewer-line failure are quite low.

While They Seem Affordable, These Plans Are Wildly Overpriced

The warranty plans we reviewed cost $4 to $13 per month. That might seem like a small price to protect against an expensive, if unlikely, problem. After all, some warranty buyers do suffer problems and are glad they signed up. “Over the past three years, more than 400,000 water-related repairs have been completed through the National League of Cities Service Line Warranty Program [a HomeServe brand], saving residents $232 million in out-of-pocket repair costs,” Meehan told us.

But HomeServe’s own numbers reveal a key issue: Divide that $232 million in repair bills by the 400,000 claimants and the average payout was just $580.

During HomeServe’s partnership with WSSC, claims for sewer line repairs also averaged just $580; the average was $1,565 for water line claims.

The 2015 filing we found with the California Department of Insurance indicated the average water-line-coverage claim was only $676; for sewer lines, it was just $430.

These real, likely repair costs reveal that although warranty companies rely on worst-case scenario scaremongering to sell their plans, “most often, the claim you put in is for a clogged [sewer] line, and the first thing they try to do is unclog it,” said Alon Abramson, program manager for the Philadelphia Energy Authority. “More often than not, that fixes the problem.”

In other words, when repairs are needed, they’re usually done by a plumber using a snake.

Checkbook often warns about these types of “peace of mind” policies. While you should buy insurance to protect against risks that could be financially catastrophic—house fires, liability claims, auto accidents, medical care—you shouldn’t bother paying to cover the risk of paying for unlikely repairs that you can afford.

There are key differences between insurance and warranties like these: “An insurance policy requires an insured event to cause the damage. A warranty pays to fix things that break,” said Sandra Watts, an advocate and program coordinator for United Policyholders, a San Francisco consumer group. So if a sewer line breaks and there’s a backup that requires tens of thousands of dollars to restore your home and replace ruined belongings, a warranty would cover repairs to the broken pipe, but not to clean up the yuck in your home.

Another reason a $4-to-$13-per-month price is too high for what you get is that a large cut of those costs go toward paying commissions to utility companies, not to pay claims.

For example, for 2020 AWR pays the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) $3.61 every month for each enrolled policy. AWR sells water- and sewer-line coverage in San Francisco for $12.99 a month. That means 28 percent of what it collects from customers there is spent not on paying claims, but to pay off the SFPUC.

The SFPUC skims the same $3.61 from AWR’s $8.99/month sewer-only warranties and its $4.49/month water-only plans. So, for those, commissions equal about 40 and 80 percent, respectively. SFPUC expects to rake in more than $1 million from this deal over its first four-year term.

“There must be a lot of fat in the premiums,” said Watts. “I was shocked by the high percent of the total premium they’re paying the SFPUC.”

AWR’s deal with the Philadelphia Energy Authority also funnels a large chunk of premiums back to it. AWR charged $7.98 a month for water-sewer warranties purchased in 2020; the PEA gets 20 percent of that, plus up to $500,000 in annual fees. In 2019, the first full year of its contract with AWR, Philadelphia’s share was $1.3 million. If the contract is renewed and 25 percent of the city’s water department customers enroll in an AWR plan, it will pay the PEA an extra $500,000, and yet another $500,000 on a second renewal if that number hits 30 percent.

Not surprisingly, the PEA doesn’t publicize all the money it gets from its deal with AWR. And it wouldn’t release to Checkbook details about its financial relationship with AWR until we fought for and won their release.

Again, the fact that so much of the money paid to warranty companies gets spread around to their utility partners suggests that warranty companies don’t expect to pay out much in claims.

“The only reason AWR can pay $1.3 million in commissions to PEA is because they’re overcharging people for this meager product,” said Douglas Heller, an insurance expert with the Consumer Federation of America.

Why Do Public Utilities Help Warranty Companies Sell This Lousy Stuff?

AWR and HomeServe clearly rely on recruiting public utility companies to help sell their warranty plans. Without this cooperation, offers sent by AWR and HomeServe would be just oft-ignored junk mail. A pitch used to recruit utility companies by HomeServe’s National League of Cities Service Line Warranty Program, states that “correspondence with the municipality’s logo is much more likely to be trusted and opened by recipients.”

“In addition to this being a lousy product, it’s a lousy product that only sells because there’s the stamp of authority on it from the utility,” said Heller.

For its part, a utility that signs on with AWR or HomeServe does very little work to earn its share of the premiums paid by its constituents. The utility typically only has to provide its endorsement and its logo.

Fortunately, most utility companies don’t get involved in this game. Of 54,000 water systems in the U.S., at the time of this writing only 1,300 partnered with AWR or HomeServe. Checkbook’s researchers reached out to the largest water utilities in the seven metro areas we serve. Of those 199 operations, 135 were not yet participating in warranty sales.

Officials with utilities we contacted offered a variety of reasons why their outfits hadn’t yet signed on with one of these deals.

“Is it predatory where you’re scaring people into something?” said Patrick Shea, assistant general manager of St. Paul (Minn.) Regional Water Services, which does not partner with warranty companies. “We provide a public service, and I don’t want to take advantage of grandma when she doesn’t need a service line warranty because her house is only 10 years old.”

The District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority evaluated these programs and decided not to participate because the plans were “not in the best interest” of customers, according to a quote published in a Washington Post story and confirmed in an email to Checkbook from John Lisle, a DC Water spokesperson.

Seattle Public Utilities was approached by AWR and HomeServe, said Kevin Burrell, a spokesperson. However, the utility has not partnered with either. But what about the money it could rake in? “Seattle is pretty conservative when it comes to that type of benefit or partnership. There are a lot of perception issues,” said Rachel Garrett, senior program manager for wastewater education and outreach.

We found only a few utilities in New England working with AWR or HomeServe. “The Boston Water and Sewer Commission is a public entity…therefore we cannot partner with private companies,” said Thomas Bagley, a spokesperson. Boston offers a better deal, anyway: one-time grants of up to $4,000 for eligible homeowners whose sewer lines have blocked or collapsed and can’t be cleared. For water-line leaks, BWSC will do the repair work and homeowners can pay for it via low-interest loans.

Many utilities that do partner with warranty companies justify their involvement by claiming they direct their shares of sales to a good cause.

“The fee is going to support our energy efficiency programs, including low-income solar and low-income housing,” the PEA’s Abramson explained.

“One of our concerns was that we didn’t want to be making money on this program,” said David Harpell, executive director of the Jackson Township (N.J.) Municipal Utilities Authority, quoted in a HomeServe promo to municipalities. To address this concern, more than $53,000 was re-directed to charities serving the township for “feeding the hungry or supporting those suffering from serious illness,” Harpell is quoted saying.

The WSSC’s 2016–2019 partnership with HomeServe also included a “HomeServe Cares” hardship fund, providing free water and sewer line repair or replacement for needy homeowners. But only 16 of 64 applicants were approved—the rest didn’t have income below 200 percent of the federal poverty guideline, didn’t have a qualifying emergency, or were already enrolled in the plan.

The SFPUC is still working on its good-deeds excuse for the more than $1 million it expects to extract from San Francisco warranty buyers’ payments. “At this time, we don’t have an exact pinpointed program, but we’re planning for some sort of low-income assistance,” Michael Tran, the commission’s project manager, told Checkbook.

Will Reisman, an SFPUC spokesperson, spins its haul as “revenue share,” and told Checkbook that “the SFPUC does not collect any money from AWR’s enrolled customers.”

Yvonne Kingman, a spokesperson for Washington (State) Water Service, told us it recycles the warranty fees it gets back to their customers: “We’re regulated. The money we collect is all used for company-related projects. We don’t pocket the money. We charge customers for the actual cost of providing the water service.”

But, of course, even if it gets directed toward a do-gooder fund, all the revenue collected by these warranty companies is derived from utilities’ cooperation in enrolling their customers in these lousy plans.

Consumer Federation of America’s Heller noted that “these deals are so clearly problematic that even those willing to take them require some veneer of justification that it is a public benefit.”

And Heller also pointed out: “When government collects money from its residents, it’s a tax, a fee, or a fine, and having the tax laundered through a warranty company doesn’t make it any less of a tax. Taxation should be done honestly and transparently.”

Checkbook’s view: We find it repugnant that a public utility would disguise one of these deals with a virtuous façade, as if the real purpose of helping to sell these terrible plans is to help the economically disadvantaged. Doing so ignores the fact that these warranties are wasteful and sold under false pretenses. Utilities shouldn’t get involved in the first place.