Last updated November 2025

Click below to listen to our Consumerpedia podcast episode.

American consumers are bombarded with seemingly great deals when shopping in-store and online. Displays and banners scream for your attention: “SALE! 60% OFF!” “Regular price: $299, our price: $199.” “This weekend only: Save an extra 40%!” “Prime Day!” “Black Friday!” “[Insert your favorite holiday] Special Savings!”

It’s all nonsense. Most retailers are lying to you.

Consumers’ Checkbook’s researchers spent six months tracking prices at 25 major retailers. We found that the markdowns advertised by most stores aren’t special prices or savings; instead, nearly all retailers now use fake sales to mislead their customers. And this shady selling practice keeps getting worse.

Websites and in-store signage for most retailers often show crossed-out “regular” or “list” prices, with lower prices featured nearby. But the higher “regular” prices are rarely, if ever, what customers actually pay. Our study found that at most stores, the products we tracked were offered at supposed discounts more than half of the time. And, at many retailers, the fake sales never end: For 12 of the 25 companies, our shoppers found more than half the items we tracked were offered at false discounts every week or almost every week we checked.

By constantly offering items at sale prices—and rarely if ever offering them at regular prices—retailers are engaging in deceptive advertising.

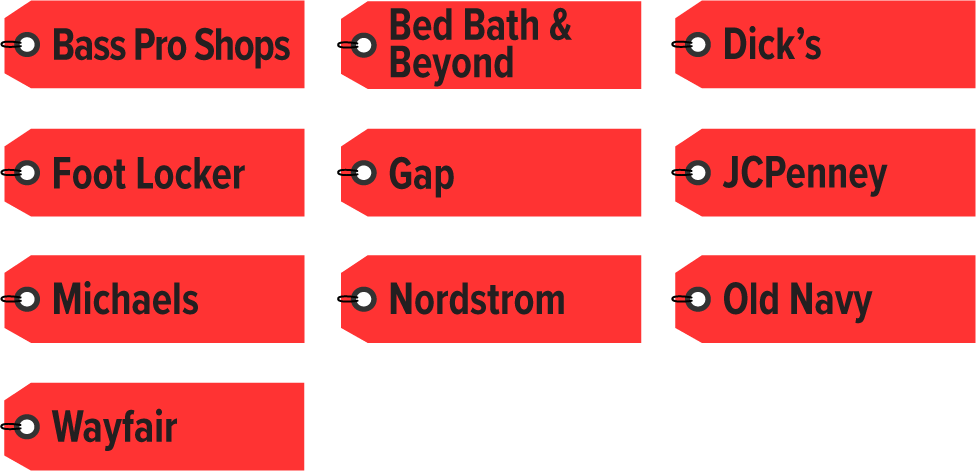

Checkbook found these retailers’ sales were Usually misleading:

Checkbook found these retailer’ sales were Often misleading:

Checkbook found these retailers’ sales were Sometimes misleading:

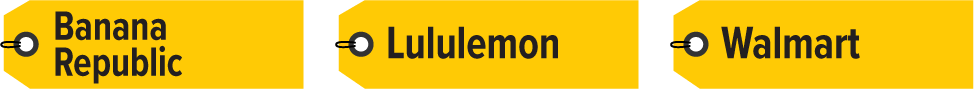

Checkbook found that only three of the 25 retailers offered Legitimate sales:

Stores run those special-but-not-really-special discounts, holiday sales, and red-dot-spring/summer/whatever-event prices to manipulate you into buying items right away for fear that prices will soon go up. These fake sales also might dissuade you from shopping around for a better deal; after all, if that shirt, blender, or TV is marked down 60 percent, why bother to compare costs?

This selling strategy is also designed to make you feel so good about what you pay that you’ll snap up more stuff while you’re at it. If you believe you’ve saved a bundle, you might keep right on buying because your perceived savings enable you to “afford to spend more.”

Beginning in February 2025, once a week for 24 weeks Checkbook’s researchers tracked the prices offered by 25 national chains for 25-plus items at each store. We selected on-sale products representative of each company’s primary offerings (for example, power tools at Home Depot, clothing and housewares at Kohl’s, big-ticket electronics at Best Buy).

This research expands on similar projects we completed in 2015, 2018, and 2022, when each time we spent 40 or more weeks tracking major retailers’ prices. Over those 10 years, fake sales have become far more prevalent. During our 2018 project, six retailers—JCPenney, Kmart, Kohl’s, Macy’s, Neiman Marcus, and Sears—offered at least half of the items we tracked at fake discounts more than half the time. Now, far more of the stores—21 out of 25—advertised sale prices more than half the time.

Some retailers still have more egregious pricing practices than others. Bass Pro Shops, Bed Bath & Beyond, Dick’s, Foot Locker, Gap, JCPenney, Michaels, Nordstrom, Old Navy, and Wayfair were the naughtiest fake-sale offenders. Most of the items we tracked at those stores were always or almost always on sale.

But nearly every store we studied was guilty of using misleading sales. Only Apple, Costco, and Dell consistently conducted legitimate discounts. (Apple’s website and stores rarely, if ever, mark down merchandise.) Walmart was a borderline case: Ten of the 24 items we tracked for it were on sale at least 50 percent of the time; overall the items we tracked at Walmart were on sale 48 percent of the time.

Banana Republic and Lululemon were outliers. Each offers discounts on only a small number of items each week, but most items we tracked were marked as “Final Sale” for the 24 weeks we checked.

The other 19 retailers labeled their items “on sale” about 76 percent of the time, on average, meaning that far more often than not they promoted prices as discounts that weren’t really special.

The table below summarizes our findings for each retailer. At each, we began by tracking prices for 25 to 30 items, but during our 24-week research period some items were discontinued. When that happened, we replaced unavailable items with comparable products and started tracking the new items. The summaries we report apply to products that were available for purchase for at least five consecutive weeks (but most were available for more than four months in a row).

Most “Regular” and “List” Prices Are Meaningless

Most retailers we studied poorly disclose how they determine crossed-out “list” prices.

On the websites for Bass Pro Shops, Dick’s, Foot Locker, Home Depot, JCPenney, Lowe’s, Lululemon, Michaels, Nordstrom, and Staples we couldn’t find any explanations of how “list” prices were set.

For the other companies, explanations were typically buried under “Terms and Conditions” sections on their websites. But Amazon, Bed Bath & Beyond, Best Buy, Macy’s, Target, and Walmart provide more transparency: With each, you can hover over list prices or click on nearby icons for definitions of how they determined their crossed-out “list” or “regular” prices.

Even retailers that provide explanations often give silly justifications. Kohl’s takes the prize for most ridiculous disclaimer. It reads, in part, “The Regular or Original price of an item is the former or future offered price for the item or a comparable item by Kohl’s or another retailer.” In other words, Kohl’s claims its discounts are based on prices that it or one of its competitors might have charged in the past or might charge in the future. Does Kohl’s have a time machine?!

Best Buy provides a similar disclosure: “Our ‘Comparable Value’ prices are based on the price at which the product, or a comparable item, was (or in the future will be) offered for sale by Best Buy, marketplace sellers, manufacturers, suppliers, or other retailers.”

If you dig, some retailers provide realistic explanations. Bed Bath & Beyond’s disclosure reads: “Median non-sale price listed for this product in the last 90 days.” But, of course, that explanation doesn’t admit that these former non-sale prices might have been offered infrequently, and perhaps never.

A few retailers do warn that you can’t believe what you see. Amazon, for example, says: “The List Price is the suggested retail price of a new product as provided by a manufacturer, supplier, or seller. Except for books, Amazon will display a List Price if the product was purchased by customers on Amazon or offered by other retailers at or above the List Price in at least the past 90 days. List prices may not necessarily reflect the product’s prevailing market price.”

Stores like Gap and Old Navy can’t defend their selling practices by pointing to “list” prices set by manufacturers, as these retailers sell only stuff they distribute.

Is This Illegal?

Retailers are violating clear-cut laws.

The Federal Trade Commission’s rules on “former price comparisons” state that discounts are illegal if the “former price being advertised is not bona fide but fictitious—for example, where an artificial, inflated price was established for the purpose of enabling the subsequent offer of a large reduction—the ‘bargain’ being advertised is a false one; the purchaser is not receiving the unusual value he expects...”

The FTC’s rules also require that when stores advertise a regular price that it “is one at which the product was openly and actively offered for sale, for a reasonably substantial period of time, in the recent, regular course of his business, honestly and in good faith—and, of course, not for the purpose of establishing a fictitious higher price on which a deceptive comparison might be based. And the advertiser should scrupulously avoid any implication that a former price is a selling, not an asking price…unless substantial sales at that price were actually made.”

The problem is widespread and continues to grow. Yet to our knowledge the FTC hasn’t bothered to enforce its own rules on this matter for decades.

Over the last 10 years we have asked several FTC officials whether they were aware of any FTC actions against companies using these illegal sales practices. None would comment on the record.

Meanwhile, the problem keeps getting worse.

Protect Yourself

Don’t assume that a sale price is a good price. The store probably offers that price—or an even lower one—much of the time.

Shop around. The only way to know if you’re getting a good deal is to compare prices offered by other retailers. Checkbook regularly finds big store-to-store price differences for the same items; it’s not uncommon for stores to charge twice as much as their competitors for the same product. We also found that, over several months, some retailers’ prices for specific items can climb or fall by as much as 100 percent. A quick internet search will usually help you determine if a store is offering a low or high price. Shopping bots like Pricegrabber.com and Yahoo! shopping can also be helpful. And CamelCamelCamel tracks Amazon’s prices.

If you find a lower price online, ask for a price match. Many stores will match lower prices offered by their competitors, even online sellers. Our researchers checked for price-matching and price-adjustment offers with about 100 major retailers and found that most offer consumer-friendly policies.

Take your time. Even if an item you’re thinking about buying really is on sale, many stores will agree to hold their lower price for you beyond the end of the sale date. Just ask.

Don’t fall for manipulative tricks. All the bogus sales and discounts are designed to make you feel good about the prices you pay and convince you to buy now and buy more. Even if you get a genuinely great deal, don’t let those savings push you to spend more on other stuff.

Call or email stores to get competitive bids. A bad-for-consumers policy enforced by manufacturers for many big-ticket products (appliances, electronics, etc.) is the use of “minimum advertised prices,” or MAP. Designed to boost profits and squelch competition for large retailers that have a lot of clout with manufacturers, these policies require retailers to advertise product prices at or above preset minimums. Because of MAP, you won’t get the best prices on most major brands of appliances from online searches or sales circulars. But MAP policies don’t apply to prices quoted to customers in person, over the phone, via email, or offered to loyalty-club members. Stores—particularly independent ones—often quote appliance prices below MAP if they know that’s what it takes to close a deal.

Use Checkbook’s ratings and tips. Our advice and ratings of stores and other local service providers for quality and price help you find the best deals from the best stores and companies.