Acupuncture History and Trends

Last updated May 2025

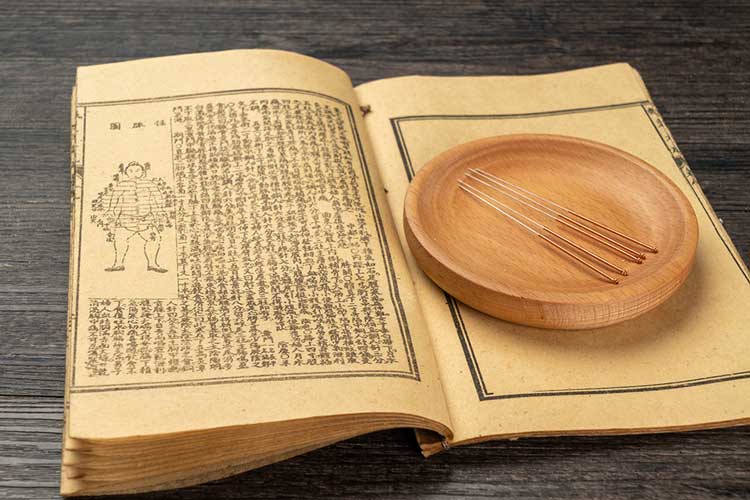

Acupuncture stimulates various body points by penetrating the skin with thin metal needles. It draws on medical traditions from China, Japan, Korea, and other Asian countries. Acupuncture was first practiced in China more than 2,000 years ago, but during the 1600s it fell out of favor and was replaced by herbal remedies. By the 1800s, Chinese medicine was science-based, but acupuncture made a comeback there in the 1950s, when China lacked financial and medical resources and sought low-cost medical treatments.

In the U.S., use of acupuncture reaches back only about 50 years. As U.S.-China relations reopened in the early 1970s, James Reston, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter, contracted appendicitis while visiting China (he just missed the scoop on Henry Kissinger’s secret meeting with Premier Zhou Enlai). After his appendectomy, Reston claimed his post-op discomfort was successfully treated with acupuncture, a story he recounted on the front page of The New York Times (headline: “Now, About My Operation in Peking”). Nixon’s visit in 1972 further spurred interest in the pins-and-needles treatment.

Western medicine generally accepts that acupuncture works by stimulating and promoting the body’s own healing processes. In Eastern medical lingo, ailments are described in terms of an excess of or deficiency in yin or yang, forces that are connected and interdependent. Energy, or qi (pronounced “chee” in Chinese), flows through the meridians or pathways of the body. These pathways connect via acupuncture points relating to internal organs; acupuncture’s specialized needle placements restore the balance of yin and yang by reducing disruptions along the meridians, improving the flow of qi and promoting healing.

Although most Americans know about acupuncture, most estimates calculate that fewer than two percent of adults in the U.S. undergo it annually.

Like many alternative medical procedures, acupuncture is also subject to trends—for example, acupuncture “facials,” that supposedly tighten jowls and increase collagen production on aging skin.

Community acupuncture, where several patients (fully clothed) lie in the same room and receive simultaneous treatments, remains popular. This group setting supposedly heightens healing; if you don’t buy that, then maybe the very low costs will tempt you; community sessions usually cost less than half of typical private treatments.

“Dry needling” or “deep tissue” acupuncture seeks to stimulate muscles and reduce pain by attaching the needles to low electric currents.

Many of its practitioners insist that while their method draws on acupuncture traditions, it is not really acupuncture. There’s a bit of controversy here: A lot of acupuncturists argue that physical therapists, chiropractors, and alternative medicine practitioners performing dry needling are calling it something other than acupuncture to avoid state licensure requirements. A handful of states, including California, Hawaii, New Jersey, Utah, and Washington, have special licensure requirements for dry-needling procedures.

The American Medical Association (AMA) categorizes dry needling as an invasive procedure, and has argued that it suffers from “lax regulation and nonexistent standards.” In 2016, the AMA adopted a policy that said “physical therapists and other non-physicians practicing dry needling should—at a minimum—have standards that are similar to the ones for training, certification and continuing education that exist for acupuncture.”