Selecting the Right Hearing Aid

Last updated November 2024

Digital technology has revolutionized hearing aids. Even basic models are vastly superior to old analog models, allowing wearers to hear in complex and varying listening environments.

Technological improvements have also made high-performing aids very small and less obtrusive to wear.

But costs keep many people from using hearing aids. Medicare and most private insurance plans don’t cover hearing aids or even testing. Until recently, the only way to buy aids was through an audiologist or other licensed hearing healthcare provider, and most patients had to pay from $2,000 to more than $8,000 per pair.

To make hearing aids more affordable, a federal law passed in 2017 instructed the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop guidelines to approve over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids, which people can buy and program themselves for a fraction of the cost charged by licensed pros. After five years of study, in 2022 the FDA finally approved the sale of OTCs. Sold online and by drugstores and big-box retailers, most are priced between $300 and $1,000 per pair.

While there are hundreds of hearing aid models available, of various sizes and degrees of sophistication, all hearing aids consist of three main parts: a microphone that takes in sound; a circuit that processes and amplifies sound; and a speaker that conveys sound to the wearer’s ear. All are powered by a small battery.

OTC Pros and Cons

While OTC aids will potentially help millions of Americans hear better, they aren’t for everyone. The FDA approved OTC aids only for treatment of mild or moderate hearing loss; those with more severe disabilities will still need to consult an audiologist or other licensed hearing instrument specialist. These patients will greatly benefit from precise testing, buying advice, access to sophisticated listening devices, fitting, and adjustments.

OTCs aren’t comparable to the cheapo drugstore reading glasses you need to read the small type in this magazine. Patients must carefully program and adjust OTCs to avoid making their condition worse, and most models offer limited adjustment capabilities compared to aids sold by hearing centers. Those with moderate or worse hearing loss will benefit more by buying aids from healthcare professionals.

OTC aids are sold by drugstores, big-box retailers, and internet sellers. Instead of visiting a specialist to get tested, choosing and getting fitted with one or two aids, and working with the provider to adjust the aids for your needs, you can buy an OTC aid and use its manufacturer’s website or app to conduct your own hearing evaluation and adjust the device yourself.

Most models cost between $300 and $1,000 per pair. There are considerable differences in features and capabilities from device to device, with the least expensive models tending to only amplify sound.

Have mild or moderate hearing loss? You still might do better using a specialist. A big downside of OTC aids is that many patients who buy them won’t get the help they really need. By not using a hearing pro, you might not get accurate testing, help selecting the best device, continued monitoring, or optimized device adjustments. Hearing loss is usually a chronic condition that worsens over time; with this type of self-care, there’s a danger that some consumers will incorrectly set their aids’ volume too high, accelerating their hearing loss.

Another downside: Because OTC aids won’t be molded to best fit your ear, they might not work as well as the customized models that specialists sell (molds can play critical roles in optimally delivering sound). And OTCs may not be as comfortable.

But OTC hearing aids are a lower-risk purchase than shelling out for expensive aids from a specialist. If your custom aids don’t work well, or you lose or damage them, you could be out thousands of dollars. If your dog eats an OTC model, it may be just a few hundred dollars to buy a new one.

Another reason for the OTC aid legislation was that many patients already DIYed their hearing health, purchasing crude devices still sold online for as little as $10. These unsophisticated gadgets usually just amplify all sound and offer little or no way to make adjustments, meaning users can crank up the volume and accelerate their hearing loss. FDA-approved OTC aids, on the other hand, offer far more adjustment capabilities and better filters.

Hearing-Aid Styles

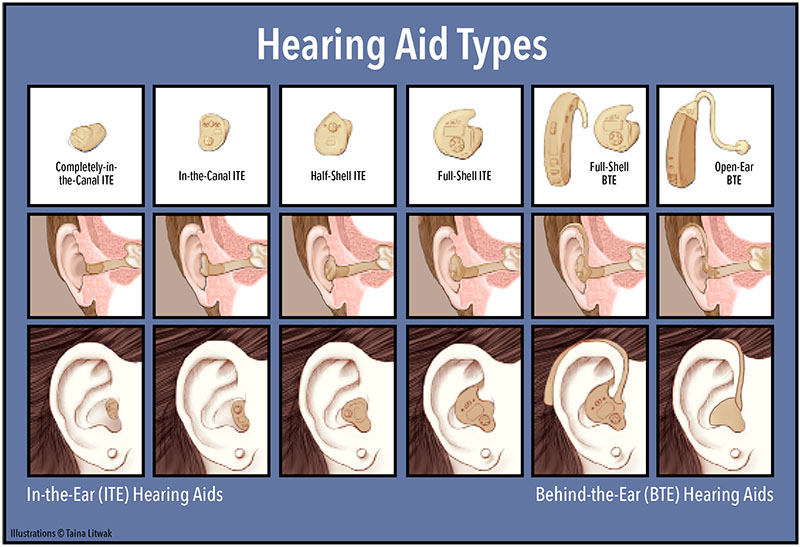

Hearing aids vary in shape, size, and the way they are worn. They range from tiny devices that nestle completely within the ear canal to larger, more visible models that sit behind the ear. Although any style may include many technologies, the smallest aids tend to have less power to address severe hearing loss. If you have moderate-to-profound hearing loss, carefully discuss your choices with your physician and audiologist.

The figure below illustrates aid styles.

The two general categories are behind-the-ear (BTE) and in-the-ear (ITE). Within these two categories are a number of subcategories:

Behind-the-Ear (BTE)

These models consist of a behind-the-ear microphone-and-circuitry component and an earmold that fills the entire ear opening to deliver sound; a tube links the two components.

“Open-fit” or “open-ear” BTE models use a small microphone instead of an earmold, leaving the ear opening largely unobstructed and allowing unaltered sounds to enter. These models are particularly good for users who have good or fairly good hearing for certain pitches but need help with others. Filling these users’ ears with earmolds would block natural sounds that could be heard without hearing aids—often contributing to a disconcerting inside-a-barrel sensation called “occlusion.” Open-fit BTEs facilitate a more normal mixture of amplified and natural sound, and a more comfortable, less occluded wearing experience.

Some open-fit hearing aids simply guide processed sound into the ear canal through a very thin tube. Other open-fit models use a wire instead of a tube and position the speaker (or receiver) at the end of the wire in the ear canal. These “receiver-in-the-canal” or “receiver-in-the-ear” models are very popular.

In-the-Ear (ITE)

With ITE models, the entire aid is worn within the ear opening or ear canal, using custom-molded devices. ITE models range in size from “full-shell,” which fill the concha (bowl) of the ear, to “completely-in-the-canal” (CIC) styles, which are almost completely hidden inside the canal. “Half-shell” styles are a bit smaller than full-shell styles, and “in-the-canal” (ITC) styles are a bit larger than CICs. “Invisible-in-the-canal” (IIC) models are seated deeply in the ear canal and not visible.

There are also extended-wear devices, which are placed into the ear canal, where they remain until the batteries expire two or three months later. They are then replaced with new devices.

Choosing a Style

Since ITE aids are smaller than BTE models, they are popular with patients who want a less visible hearing aid. But newer BTE models are smaller, and open-fit technology makes BTE aids more appealing than before. On the other hand, some patients prefer ITE aids because they are compact and keep everything contained within the ear.

If you have severe hearing loss, you’ll probably buy a BTE style, since ITE aids can’t deliver the power you’ll need. Also, BTE aids tend to be more reliable than ITE models, and BTE aids have space for larger easier-to-operate controls.

Features to Consider

Some OTC models are very basic and simply amplify certain types of sound, but some offer advanced capabilities—for a higher price.

More sophisticated hearing aids, even “entry-level” ones from hearing specialists, incorporate technology such as directional microphones, automatic volume control, and multiple processing channels and programs that adjust sound output to account for different listening environments.

Non-basic features—which usually drive up costs—include:

- Remote microphones that let hearing aids receive a Bluetooth or other signal. This is especially nice when using a phone, computer or tablet, or Bluetooth-equipped TV.

- Remote controls allow manual adjustment of volume, program switching, and other settings using a smartphone app or small remote. These are especially helpful for patients with dexterity issues that make it difficult to press tiny buttons.

- Communication between hearing aids enables right- and left-side aids to share information that can optimize hearing response in certain settings, particularly noisy environments. Some hearing aids use this communication to synchronize manual volume adjustments and program changes; when the wearer changes a setting on one ear, it will automatically make the same change to the other.

- Rechargeable lithium ion batteries eliminate the need to change batteries—you just place your aids on a charger at night.

- CROS (contralateral routing of signal) adaptation is a system used by people with unilateral hearing loss (hearing loss primarily in one ear) whereby a microphone for the ear with poor hearing sends sound it receives to the other ear. Instead of trying to compensate for hearing loss on one side by amplifying sound on that side, sounds that that ear should hear are delivered largely unchanged to the ear that can hear them. But this set-up requires wearers to be patient to get used to a new way of listening.

Because more advanced hearing-aid features usually mean higher prices—$3,000 or more per single aid—think carefully about whether or not that special feature is worth it. Factors to consider include the severity of your hearing loss and your lifestyle. For example, if you lead a relatively quiet life and won’t often benefit from an aid with advanced sound processing, you’ll need a different device than someone who frequents noisy parties, conferences, or restaurants.

One Aid or Two?

Have hearing loss in both ears? You’ll need two aids. The benefits are significant: They will improve your balance and safety by letting you more easily localize and differentiate sounds, and make it easier for you to understand speech in noisy environments.

Review Ratings

HearAdvisor.com, founded by two audiologists and a scientific advisor, regularly conducts independent testing of prescription and OTC hearing aids. At the time of this writing, its website provided scores for about 50 devices, with eight OTC models and 10 prescription models earning its “Expert Choice” award. Among tested OTC aids, HearAdvisor in general found that mid- and high-priced OTC hearing aids performed better than the lowest-cost options.

Consumer Reports has also tested 10 OTC hearing aids models by examining their sound distortion levels and evaluating size and ease of use. In its most recent review, it did not provide rankings; CR instead provided pros and cons for each device.

Consumer Reports does not test individual prescription hearing-aid models, but it does survey its members about devices they use and publishes customer satisfaction rates of device manufacturers.