How Marketers Trick Kids, and Why Parents Should Worry

Last updated December 12, 2025

Click below to listen to our Consumerpedia podcast episode.

America’s children have enormous spending power. Most have cash or access to their parents’ credit cards—and plenty of influence over what the family buys through their “pestering power.” Marketers know this, which is why they spend billions of dollars a year targeting minors.

It’s estimated that 42 percent of all household spending in the U.S. is influenced by eight- to 14-year-olds, according to a recent report by DKC, a New York public relations firm. These so-called “Gen Alpha” children directly spend $101 billion per year, in addition to the influence they have over their parents’ spending, the report found.

Advertising can easily exploit a child’s limited ability to distinguish between entertainment and selling—even when required disclosures are made. AI and digital animation make it easier than ever for advertisers to cross that line. With children spending hours a day on social media platforms, marketing dollars are following them.

Bonnie Patten, executive director and co-founder of the nonprofit advocacy group Truth in Advertising (TINA.org), said some companies are following the rules and regulations designed to protect children from advertising abuses (see the section “Government Regulations,” below, for a summary of laws). But she told Checkbook’s Consumerpedia podcast that she is also seeing “a lot of bad actors and deceptive marketing that has followed these kids to the internet and social media platforms.”

“The deceptive ads and manipulative ads we’re seeing can influence kids’ behavior,” Patten said. “It can encourage them to engage in risky or unhealthy or even at times dangerous behavior as a result of what they’re seeing.”

Advergames: A Sneaky Way to Market to Kids

Advergames, which are video games created to promote brands or products by integrating advertising messages into gameplay, have become an increasingly popular way for companies to target children.

These games weave logos, products, licensed characters, and mascots into gameplay, delivering a marketing message that blurs the line between entertainment and traditional marketing.

Examples of advergames include McDonald’s Treasure Land Adventure, Doritos VR Battle, M&M’s Minis Madness, and Chex Quest.

Many advergames collect user data and track behavior, allowing companies to target players more effectively.

Critics say this combination of hidden advertising and data collection can shape kids’ preferences and loyalty long before they’re able to understand or evaluate the marketing behind it.

Major national brands have launched advergames on the popular Roblox and Minecraft virtual world platforms. Offerings range from Chipotle Burrito Builder to Hyundai Mobility Adventure.

Hyundai said its game is “targeted at young consumers who are technologically savvy.” In a news release, the company said Hyundai Mobility Adventure “aims to nurture long-lasting relationships with fans” by familiarizing them with Hyundai Motor’s products and future mobility solutions.”

Major corporations, including McDonald’s, Walmart, and Samsung, have launched advergames that appeal to Roblox’s young player base, according to the Guardian. Some of these advergames on Roblox have been played hundreds of millions of times, the paper reported.

Another Major Concern: Kid Influencers

Many social media influencers are children selling to other children. Patten criticizes companies for providing kid influencers with products that are inappropriate for children, such as energy drinks, alcohol mixers, anti-aging products, weight loss products, and supplements.

“It’s a true disaster,” Patten said. “This is brands, I think, exploiting minors to get to other kids and get their products out there.”

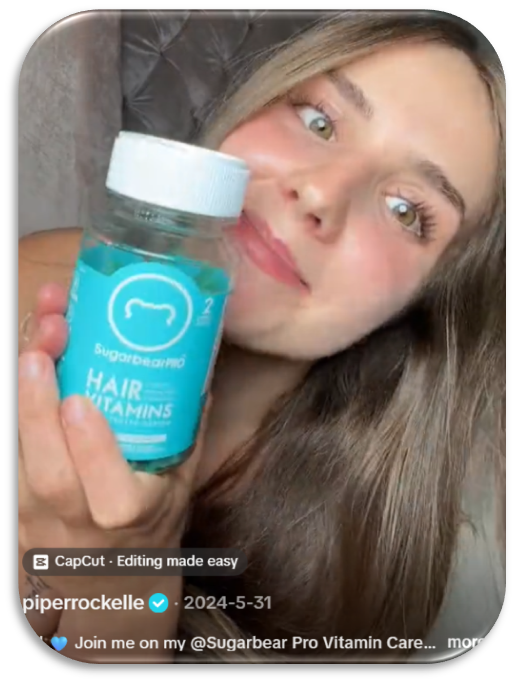

TINA.org warns parents about kid influencers in a series of reports titled Monetizing Minors. One case study focused on Piper Rockelle, an 18-year-old with more than 35 million social media followers. Her YouTube page says her videos are “great for boys and girls of all ages.”

TINA.org warns parents about kid influencers in a series of reports titled Monetizing Minors. One case study focused on Piper Rockelle, an 18-year-old with more than 35 million social media followers. Her YouTube page says her videos are “great for boys and girls of all ages.”

Rockelle mostly sells nutritional supplements and weight loss products. Many are not meant for children.

“It’s more than wrong,” Patten said. “It can absolutely be dangerous and harm kids.”

Dona Fraser, senior vice president at BBB National Programs, an independent nonprofit organization that oversees the Children’s Advertising Review Unit (CARU), is concerned that some companies don’t feel responsible for what kid influencers do.

“A lot of brands will say to us, we have no control over the influencers,” Fraser said on Checkbook’s Consumerpedia podcast, even when they hire the influencer to pitch their product or service. “Influencers are exactly what they say they are … and brands are fully aware of the power of influencers.”

Government Regulations

This is a regulated marketplace with rules that must be followed. The Federal Trade Commission enforces the FTC Act, which prohibits deceptive advertising and marketing to anyone—including children.

When deciding whether to take legal action against a company, the FTC examines the ad from the viewpoint of a child in the age group to which the toy was targeted. For example, a child might expect a toy to perform as shown in an ad, while an adult would understand that special techniques were used.

The FTC also administers the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), enacted in 2000 and updated in 2025, which prohibits the collection of personal information online or via mobile app from children under 13 without verifiable parental consent.

Under the amended rule, personal information is more than just a full name, birthdate, email address, location, and device ID. It includes biometric identifiers (such as fingerprints, handprints, retinal patterns, voiceprints, and facial recognition) and government-issued documents, such as Social Security or passport numbers.

COPPA also requires clear disclosure of what data is collected, how it will be used, and with whom it will be shared. Companies are prohibited from storing children’s personal information longer than reasonably necessary to fulfill the specific purposes for which it was collected.

In recent years, the FTC has sued major corporations for COPPA violations, including Amazon, Microsoft, and Epic Games. In September, Disney agreed to pay $10 million to settle FTC allegations that it allowed the collection of personal data from children under 13 through child-directed YouTube videos without proper parental notice and consent.

Voluntary Regulation

In 1974, the advertising industry created a voluntary system, the Children’s Advertising Review Unit (CARU), to promote responsible advertising to children and work with companies that cross the line from creative to deceptive. CARU’s key requirements are:

- Ads must be easily recognizable as advertising

- Advertising should be truthful and appropriate for its intended young audience

- Clear separation between advertising and content

- Disclosures of material connections (e.g., in influencer marketing) must be clear, conspicuous, and in child-friendly language.

- Advertising that coerces children into viewing ads or making in-app purchases is prohibited.

- Options to close, skip, or exit an advertisement must be obvious and easily understandable to children.

When a company doesn’t follow the guidelines, CARU explains the problem and what needs to be done to come into compliance. Most companies honor CARU’s findings. If they don’t, CARU can forward their case decisions to the FTC or a state attorney general.

What’s a Parent to Do?

Parents and guardians play a significant role in protecting their children from deceptive advertising and intrusive data collection. The experts recommend discussing ads with your kids based on their age. Teach them to be skeptical about marketing messages and not believe everything they see and hear.

Be familiar with what your children are watching and the platforms they’re on. And learn how to use parental controls to limit data collection or block in-app purchases.

“There’s no silver bullet; there’s no panacea here,” Fraser said. “I don’t think parents should be expected to go it alone. The entire ecosystem needs to do better.”

If you see an advertisement that you believe is harmful or deceptive, file a complaint with CARU and the Federal Trade Commission.

Contributing editor Herb Weisbaum (“The ConsumerMan”) is an Emmy award-winning broadcaster and one of America's top consumer experts. He has been protecting consumers for more than 40 years, having covered the consumer beat for CBS News, The Today Show, and NBCNews.com. You can also find him on Facebook, Blue Sky, X, Instagram, and at ConsumerMan.com.